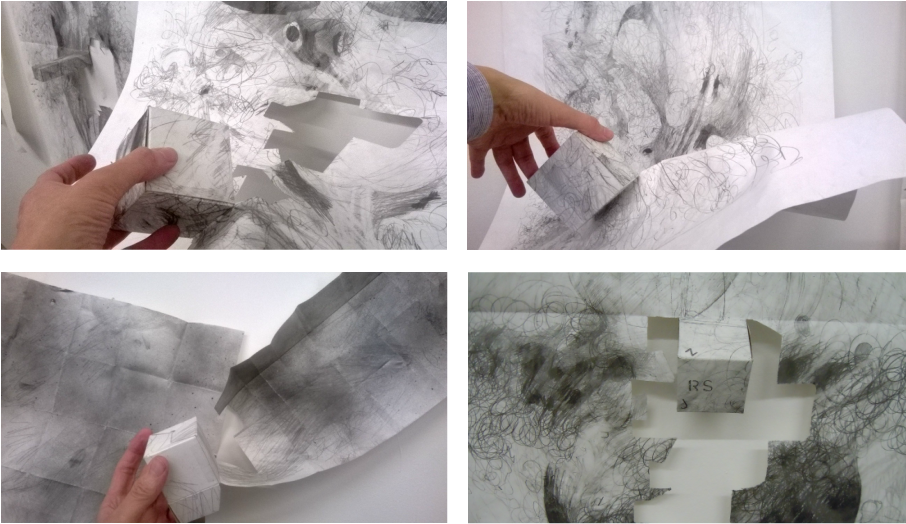

For the exhibition paper, table, wall & after I imagined my drawings unprotected by my knowledge of art. A dream recorded by Vladimir Nabokov helped. The author is in a major art museum where a curator is showing him a set of drawings under consideration for an exhibition of contemporary ‘works on paper’. The selection is laid out on a table. The author demonstrates his appreciation by eating everything he is shown. Whilst the curator clearly treasures the drawings, no indication is given that anything is wrong as the works disappear one by one. The dream closes with the author wondering about effective ways of recovering what he has just swallowed.

paper, table, wall & after (extract from exhibition text), Dorsett & Bowen (curators), Gallery North, Newcastle Upon Tyne (2014)

'after' - book-like works on paper (detail), Dorsett & Bowen (curators), paper, table, wall & after, Taiwan National University of Arts, Taipei (2015)

Hi, here is the email I promised. I am wondering if you could spare some time to tell me about the conceptual spaces occupied by your novels - once they are written - when they are published. As I said when we met the other day, my drawings in paper, table, wall & after seem to me 'like' books. I imagine they could have an afterlife similar to the publications on my library shelves. One book in particular comes to mind, it has been with me since 1971. This is the startling red catalogue to Tantra, an Arts Council exhibition curated by my mentor and friend Philip Rawson.

Of course, my drawings do not directly refer to this book, and certainly no illustrative dimension is intended, but scribbling across sheets of folded paper does seem to suggest a future that mirrors my ownership of this catalogue. After paper, table, wall & after it would be possible to take possession of one of my folded drawings, keep it on a shelf and occasionally spread it out on a table to look at like a book. If this idea is of any interest, a conversation would certainly be helpful to me. Best wishes, Chris

Of course, my drawings do not directly refer to this book, and certainly no illustrative dimension is intended, but scribbling across sheets of folded paper does seem to suggest a future that mirrors my ownership of this catalogue. After paper, table, wall & after it would be possible to take possession of one of my folded drawings, keep it on a shelf and occasionally spread it out on a table to look at like a book. If this idea is of any interest, a conversation would certainly be helpful to me. Best wishes, Chris

'after' - six unsent emails (extract), Dorsett & Bowen (curators), paper, table, wall & after, Taiwan National University of Arts, Taipei (2015)

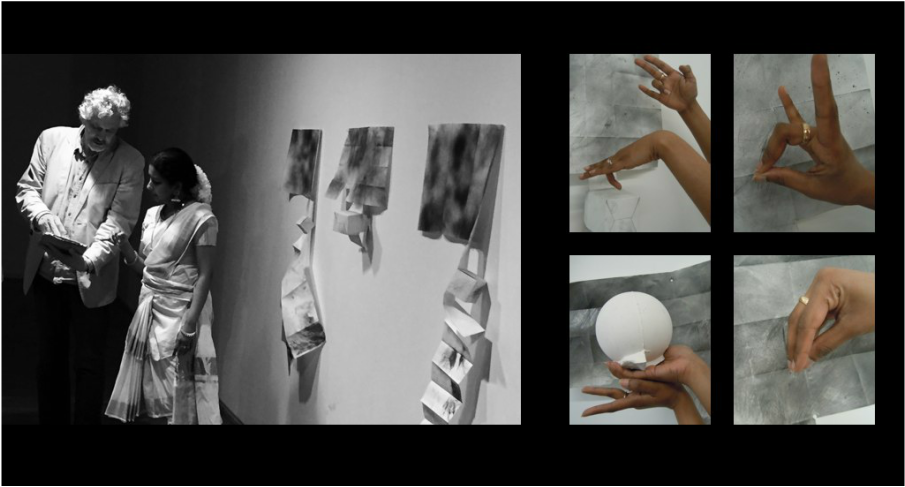

Dorsett & Nair preparing for events associated with Contemporary British and Indian responses to the 'seductiveness' of Tantric museum objects (2016). See 'speaking'

In 1971 London’s Hayward Gallery hosted a unique museological experiment in which a major venue for ‘contemporary art’ (the term was only just beginning to have currency) presented a large-scale exhibition of historical Indian artefacts as a primer for a radical reassessment of Western sexual values. The exhibition was called Tantra and, looking back, one can only wonder at the project’s ambition and the breadth of its appeal. Given the prominence of the venue, the show was reviewed (always with enthusiasm) by the most influential art critics of the day. It was also roundly endorsed in periodicals associated with alternative approaches to health and lifestyle (burgeoning at the time). In addition, it was applauded by journalists writing for various adult magazines (proliferating in the post-60s period). Thus Tantra appears to be an exhibition irreversibly caught in its historical context.

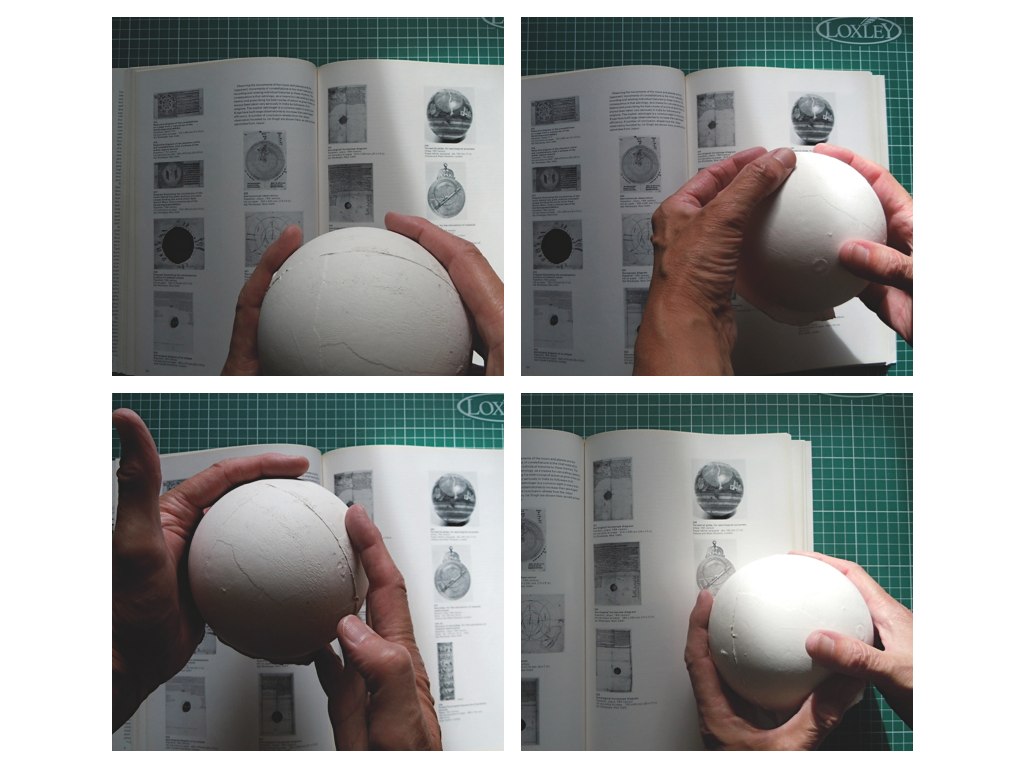

Not so. This lecture explores how practice-research methods regularly used at Northumbria University can repeat the Tantra experiment as part of an ongoing critical ‘decreation’ (Ann Carson’s term) of contemporary art. As a postgraduate student at the Royal College of Art I visited the Hayward Gallery to view Tantra’s labyrinth of strangely coloured rooms and utterly unfamiliar objects. The curator of the show, Philip Rawson, certainly anticipated the future sweep of installation techniques with sound environments and slide-tape projections, but he did this in such a way that the museal, with its gravitational pull towards the persistence of objects, deactivated the trope of avant-garde experimentation. A year later Rawson joined the Royal College staff and I became a committed student of the exchange of ideas between contemporary art and museum display. Four decades on I can return to his Tantra exhibition with extensive experience of collection-oriented work across an emphatically post-colonial world. As a result, my first public lecture at Northumbria since becoming a Professor of Fine Art is an opportunity to revisit Rawson’s early impact on my career. It is also a chance to uncover a local dimension to Tantra (Rawson was based at Durham’s Oriental Museum during the period in which the exhibition was planned and realised) and, finally, reconsider the problematic notion of Tantric ecstasy within current cross-disciplinary debates about sensual cultures and embodied meanings.

The lecture includes video material from my collaboration with Janaki Nair, a Kathakali dancer who is helping me explore the tensions between the Western fascination with Tantra and contemporary Indian attitudes to the ‘long 1960s’. I tell her my memories of viewing the multi-sensory environments Rawson created at the Hayward and she interprets my descriptions with body language shaped by a lifetime of training in Kathakali theatre. We develop events and video pieces together using the drawings and casts I have made as substitutes for the museum pieces Rawson selected from collections in the UK and India. We use our hands more than our eyes. Thanks to Janaki the scope I had in 1971 to view the Hayward exhibition has been transformed into an ability to 'handle' Tantra in the 21st century.

Not so. This lecture explores how practice-research methods regularly used at Northumbria University can repeat the Tantra experiment as part of an ongoing critical ‘decreation’ (Ann Carson’s term) of contemporary art. As a postgraduate student at the Royal College of Art I visited the Hayward Gallery to view Tantra’s labyrinth of strangely coloured rooms and utterly unfamiliar objects. The curator of the show, Philip Rawson, certainly anticipated the future sweep of installation techniques with sound environments and slide-tape projections, but he did this in such a way that the museal, with its gravitational pull towards the persistence of objects, deactivated the trope of avant-garde experimentation. A year later Rawson joined the Royal College staff and I became a committed student of the exchange of ideas between contemporary art and museum display. Four decades on I can return to his Tantra exhibition with extensive experience of collection-oriented work across an emphatically post-colonial world. As a result, my first public lecture at Northumbria since becoming a Professor of Fine Art is an opportunity to revisit Rawson’s early impact on my career. It is also a chance to uncover a local dimension to Tantra (Rawson was based at Durham’s Oriental Museum during the period in which the exhibition was planned and realised) and, finally, reconsider the problematic notion of Tantric ecstasy within current cross-disciplinary debates about sensual cultures and embodied meanings.

The lecture includes video material from my collaboration with Janaki Nair, a Kathakali dancer who is helping me explore the tensions between the Western fascination with Tantra and contemporary Indian attitudes to the ‘long 1960s’. I tell her my memories of viewing the multi-sensory environments Rawson created at the Hayward and she interprets my descriptions with body language shaped by a lifetime of training in Kathakali theatre. We develop events and video pieces together using the drawings and casts I have made as substitutes for the museum pieces Rawson selected from collections in the UK and India. We use our hands more than our eyes. Thanks to Janaki the scope I had in 1971 to view the Hayward exhibition has been transformed into an ability to 'handle' Tantra in the 21st century.

Tantric Ecstasy, Museum Culture, and Contemporary Art (synopsis), Northumbria University Public Lectures (November 2015)

Archiving Mudra – Handling Tantra (2015), 'The Earth is Breaking Up' storyboard, Contemporary British and Indian responses to the 'seductiveness' of Tantric museum objects. See 'speaking'

Despite the primeval idyll that humans associate with the kingdom of the animals, any creature that sleeps in the depths of a beautiful forest is likely to dream anxiously about the destruction of their precious environment. And so it came to pass that a hare, having fallen asleep under a huge banyan tree, awoke suddenly when he heard a loud, calamitous, crashing noise. “My dream is true,” the terrified creature thought, and taking no time to consider an escape route, he scarpered off at the kind of speed only hares can manage. As he dashed through the forest, every other hare he encountered was given the terrible news and, very soon, thousands were fleeing the forest shouting: “run, run, run – the earth is breaking up, the earth is breaking up, the earth is breaking up, we may all drown.”

On seeing an entire species running scared, other animals became frightened too. The news spread quickly and very soon every creature around the forest knew that the earth was breaking up. It didn’t take long before countless reptiles, birds, and even insects were racing to safety, and as they raced, their fearful cries created chaos around them.

Eventually, on hearing the commotion, a lion wondered what was going on. She positioned herself in the path of the panicking animals and, standing firm, halted the advance of the unruly crowd. When a parrot yelled “Quick, out the way, we must all flee, the earth is breaking up and we may drown,” the lion naturally wanted to know who had spread the rumour. “It was the monkeys,” the bird replied. But when the lion sought an explanation from from a group of over-excited chimpanzees, they were sure the news came from the tigers, not them. Despite this, the tigers, when quizzed, thought they heard it from the elephants. The elephants, in turn, said that the buffaloes were their source. And so it went on. When the chain of accusations finally led back to the first hare, the lion wanted to know why such a terrifying idea had been allowed to send shock waves through the animal kingdom. “Well, your majesty,” said the hare, “I heard the earth cracking apart with my very own ears.” And so the lion walked to the forest where she found a large coconut lying in a pile of rocks. Falling from its tree, it had caused a small, inconsequential landslide.

Waving and Drowning: at the conjunction of contemporary British and Indian responses to a song by Rabindranath Tagore (forthcoming publication). Adaption of a traditional jataka tale (extract)

Cafe Kathakali (forthcoming event). Storyboard from Dorsett & Nair's talkstudio conversation 'When Philip Rawson met Ajit Mookerjee